Here are the paragraphs you wrote in response to the “interpretive problems” considered last week. Good work, everyone!

1) Why does Rankine use a second-person speaker in Citizen?

A friend argues that Americans battle between the “historical self” and the “self self.” By this she means you mostly interact as friends with mutual interest and, for the most part, compatible personalities; however, sometimes your historical selves, her white self and your black self, or your white self and her black self, arrive with the full force of your American positioning. Then you are standing face-to-face in seconds that wipe the affable smiles right from your mouths. What did you say? Instantaneously your attachment seems fragile, tenuous, subject to any transgression of your historical self. And though your joined personal histories are supposed to save you from misunderstandings, they usually cause you to understand all too well what is meant. (14)

In Citizen, Claudia Rankine uses second person in order to make you accountable and a participant in this piece of literature. Citizen is a poem about how racism is articulated in American society and by using “you” she wants us to stop and question ourselves. Has this happened to me? She uses the second person in the quote from page 14, about meeting a person and interacting as a prospective friend: “Sometimes your historical self, her white self and your black self, arrive with the full force of your American positioning.” That word “positioning,” and the use of “you,” is all about where you, as a reader, stand in this situation, knowing someone for the first time and realizing “historical” differences due to many things: such as gender, race, and class.

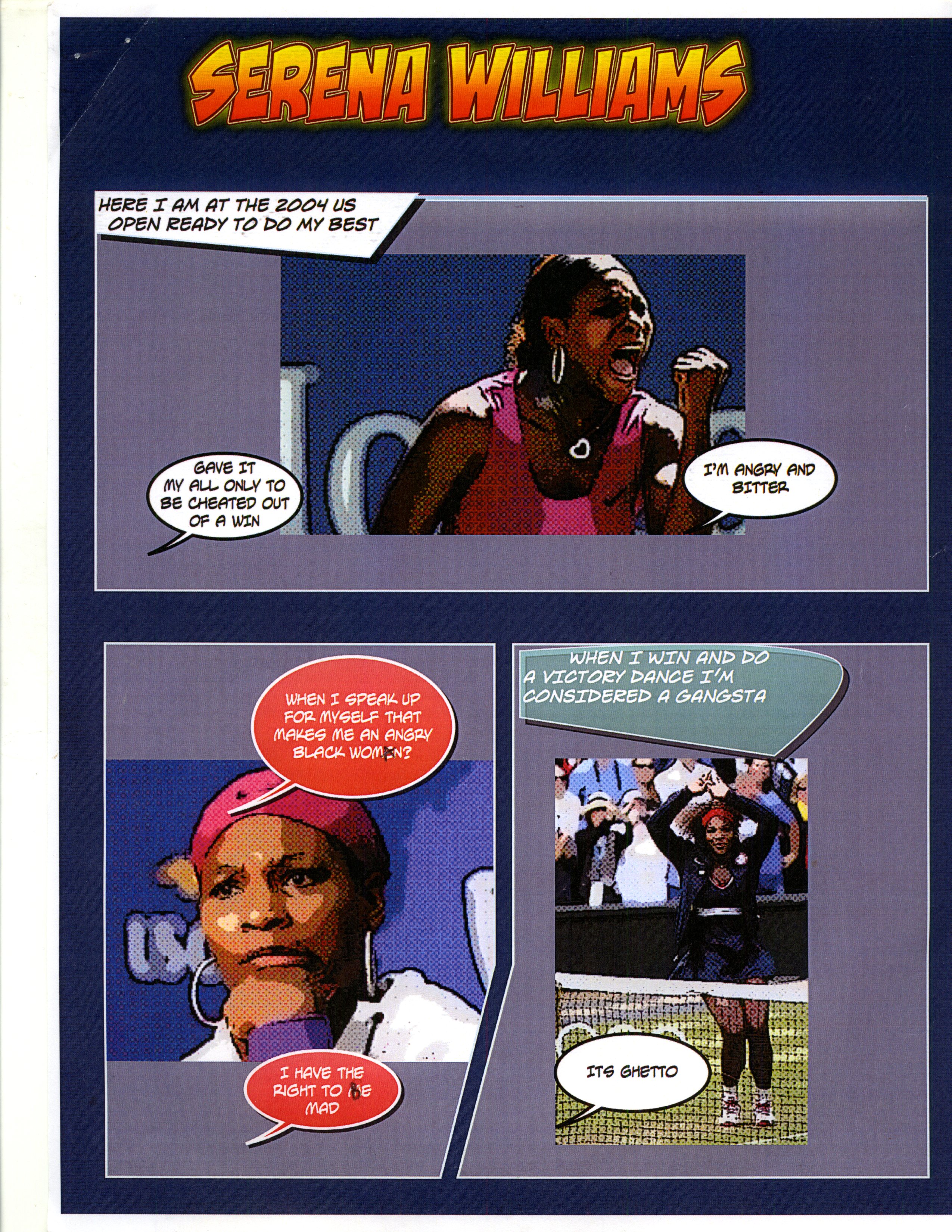

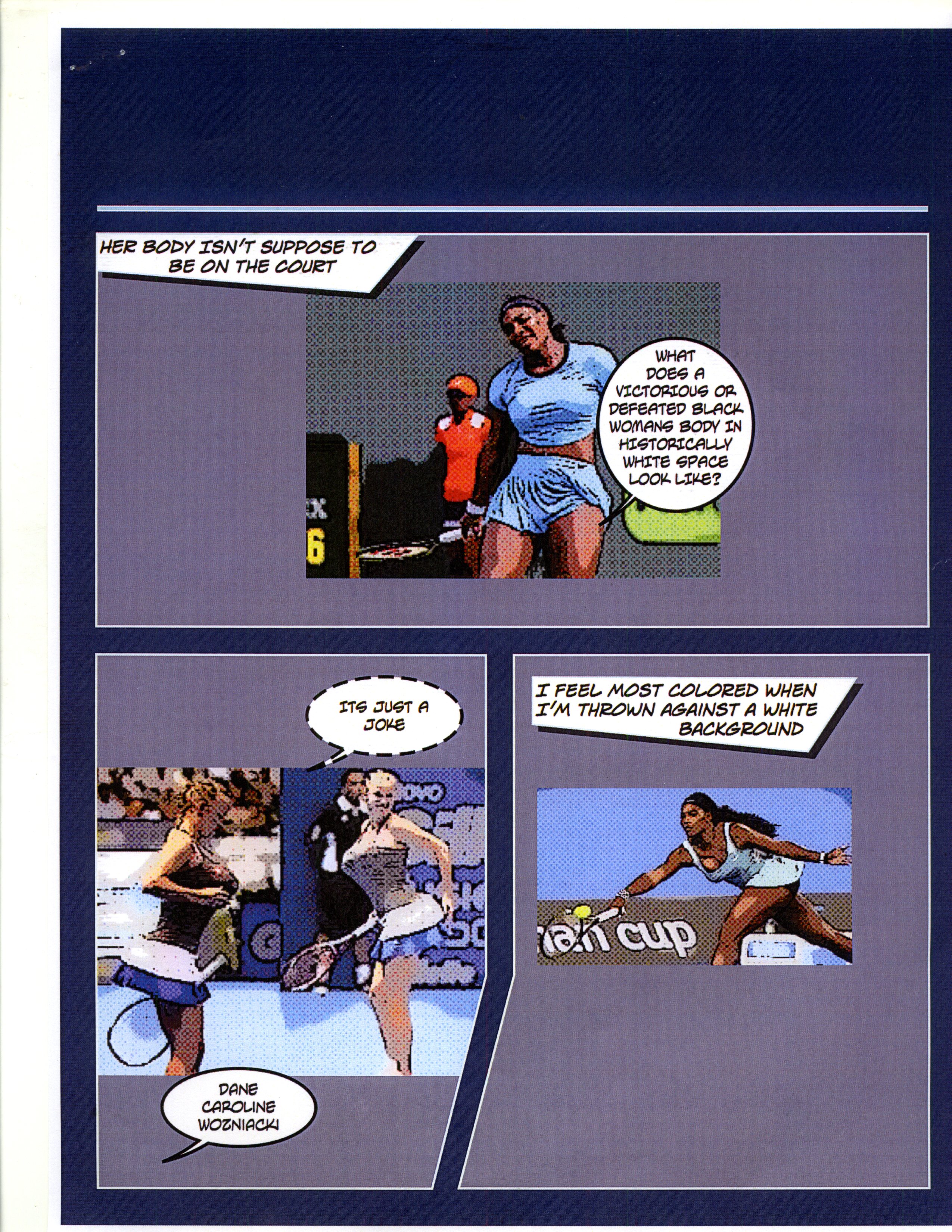

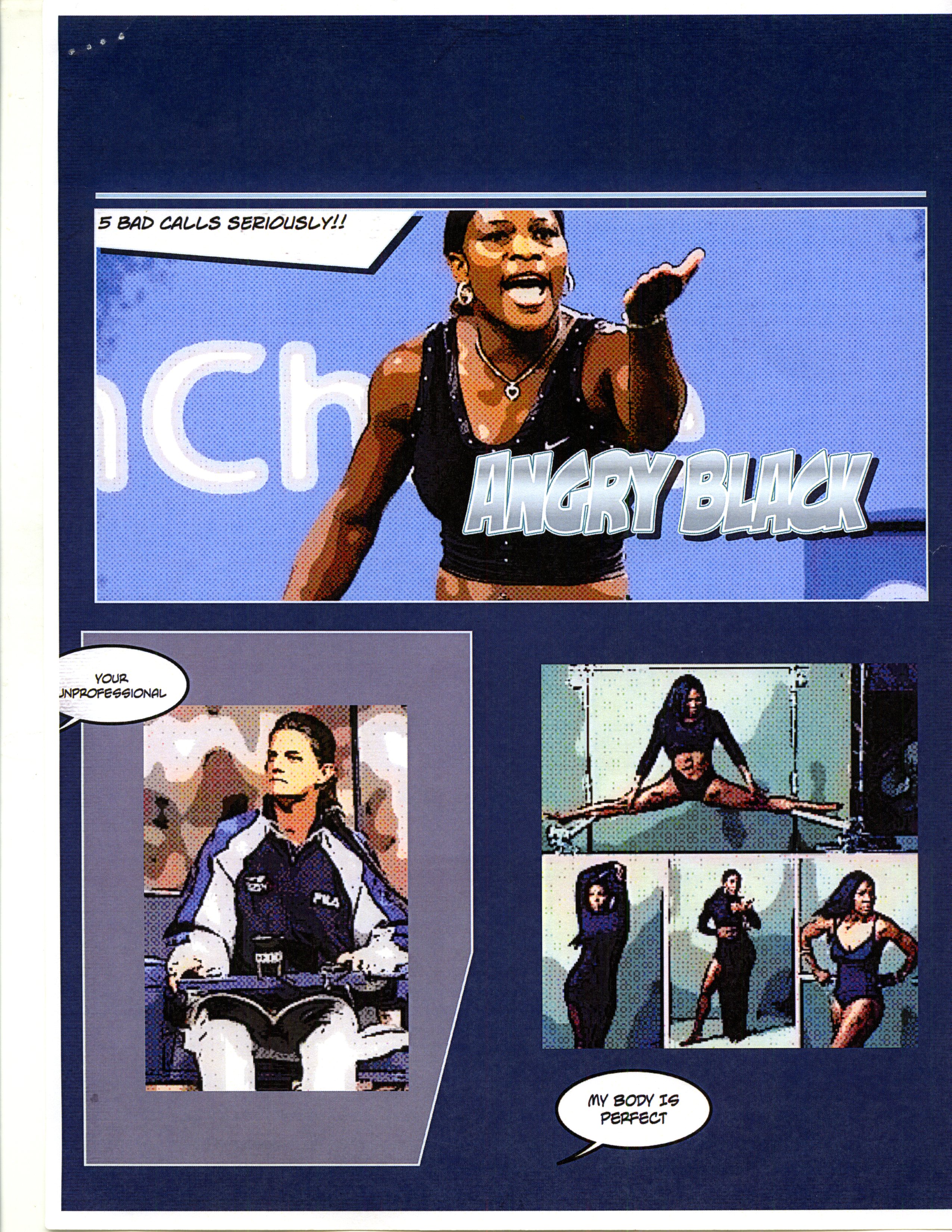

2) How does Rankine’s depiction of Serena Williams relate to the book’s broader engagement with themes of American racism?

As you look at the affable Kim Clijsters, you try to entertain the thought that this scenario could have played itself out the other way. And as Serena turns to the lineswoman and says, “I swear to God I’m fucking going to take this fucking ball and shove it down your fucking throat, you hear that? I swear to God!” As offensive as her outburst is, it is difficult not to applaud her for reacting immediately to being thrown against a sharp white background. It is difficult not to applaud her for existing in the moment, for fighting crazily against the so-called wrongness of her body’s positioning at the service line. (29)

From this passage, we believe that the author is trying to use the situation with Serena Williams as a representation of how racism is built into the American system. When the phrase “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background” is said, it represented that the game of tennis positioned Williams’ body as not belonging on the court. The “white background” represented the tennis court, which is positioned as a “white” space. This shows how institutional racism is. The sport can be played by all, but because the umpire had issues with Williams’ “black body,” she was given five bad calls and was treated differently on the court. This could relate to stop and frisk, because the umpire had the power and was able to dictate how the “rules” should be applied even though it was unfair: just like how police can stop and frisk people because they have the power to enforce rules about which bodies “belong” in certain spaces, no matter how unfair.

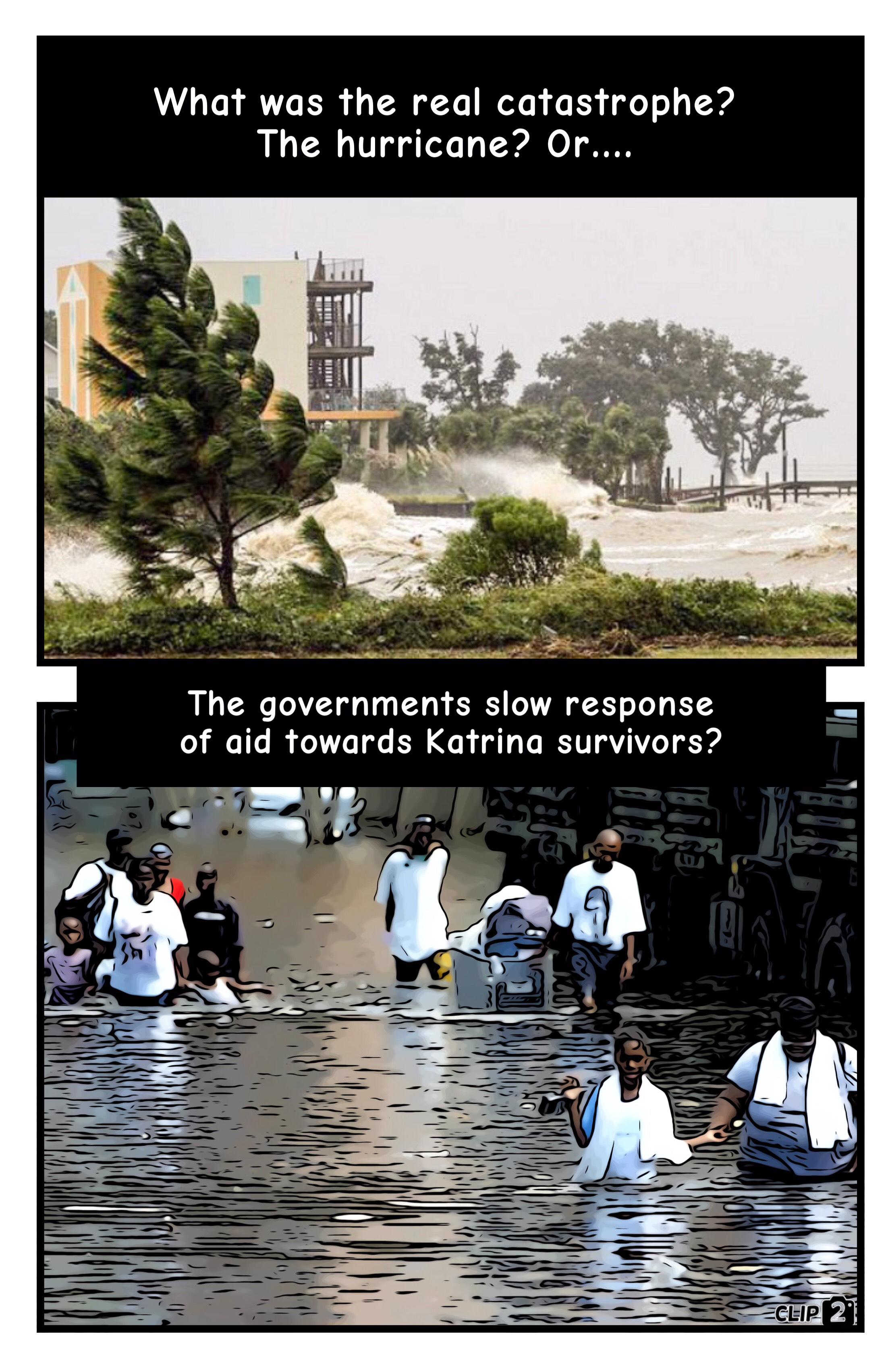

3) What is the effect of creating a poem about the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina using copy-and-pasted quotes from CNN?

Hours later, still in the difficulty of what it is to be, just like that, inside it, standing there, maybe wading, maybe waving, standing where the deep waters of everything backed up, one said, climbing over bodies, one said, stranded on a roof, one said, trapped in the building, and in the difficulty, nobody coming and still someone saying, who could see it coming, the difficulty of that.

The fiction of the facts assumes innocence, ignorance, lack of intention, misdirection; the necessary conditions of a certain time and place.

Have you seen their faces? (83)

The way CNN and other news outlets covered the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans is different from how other places would have been covered. If it was some place rich and white, the aftermath would have been described differently. The quotes Rankine uses describe the aftermath as a natural disaster, using words such as “ignorance” and “misdirection.” This language shows “invisible” racism because it ignores how neglect for black and poor communities preceded the hurricane and refuses to assign blame for that neglect.

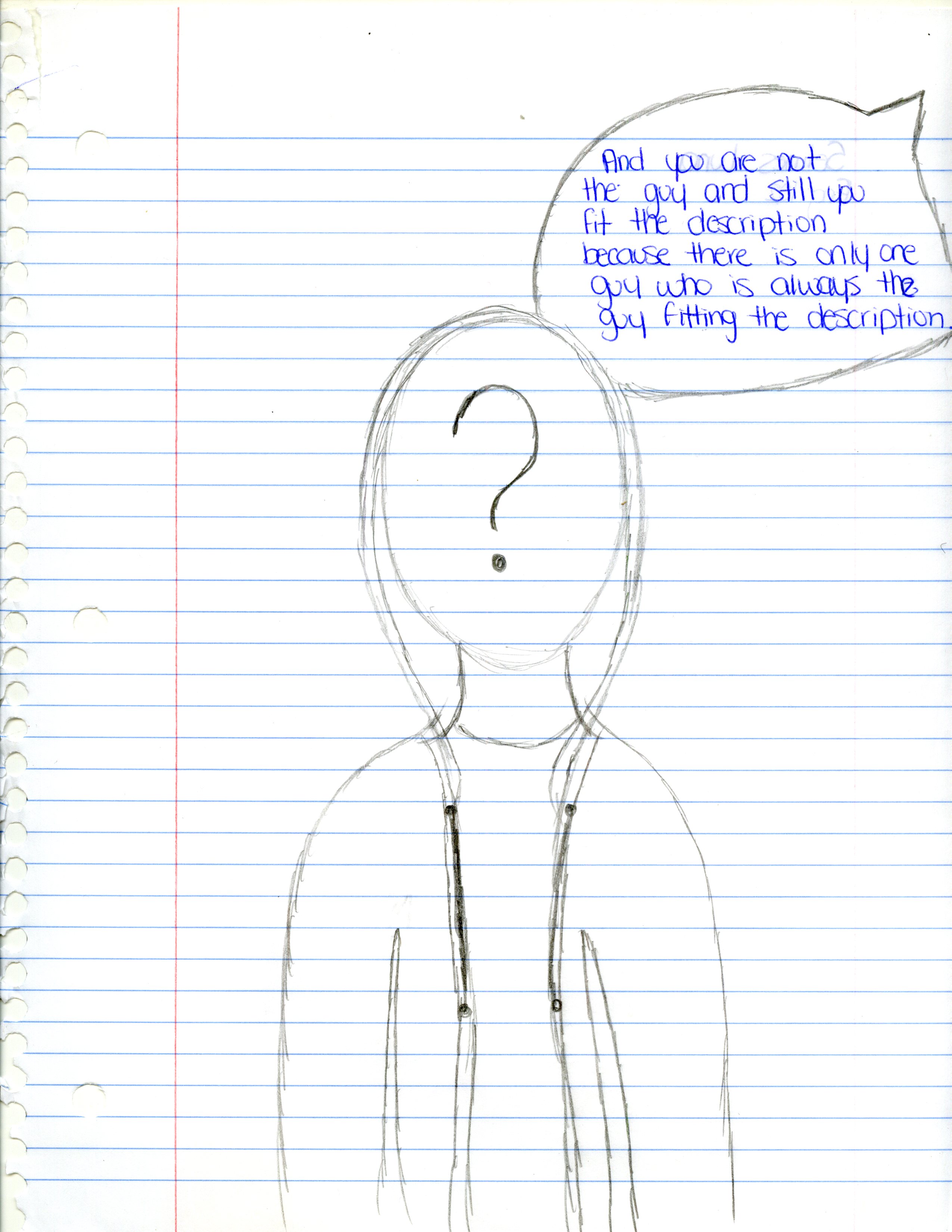

4) Why does Rankine repeat so many phrases, sometimes with small variations, in the poem “Stop and Frisk?”

Then flashes, a siren, a stretched-out roar—and you are not the guy and still you fit the description because there is only one guy who is always the guy fitting the description.

Get on the ground. Get on the ground now. I must have been speeding. No, you weren’t speeding. I wasn’t speeding? You didn’t do anything wrong. Then why are you pulling me over? Why am I pulled over? Put your hands where they can be seen. Put your hands in the air. Put your hands up.

Then you are stretched out on the hood. Then cuffed. Get on the ground now.

Each time it begins in the same way, it doesn’t begin the same way, each time it begins it’s the same. Flashes, a siren, the stretched-out roar . . .

Each time it begins in the same way, it doesn’t begin the same way, each time it begins it’s the same.

Go ahead hit me motherfucker fled my lips and the officer did not need to hit me, the officer did not need anything from me except the look on my face on the drive across town. You can’t drive yourself sane. You are not insane. Our motion is wearing you out. You are not the guy. (107)

Rankine repeats phrases to emphasize discrimination, the speaker’s confusion, and the aggression coming from the officer. Discrimination is displayed in the line, “You are not the guy and still fit the description because there is only one guy who is always the guy fitting the description.” Although the person being pulled over is not the person being sought, they fit the description of being a black man. When Rankine repeats the line, “Get on the ground. Get on the ground now,” it is to emphasize the aggression in the officer’s tone when addressing the person being pulled over. In the repeated contradictory lines, “Each time it begins the same way, it doesn’t begin the same way, each time it begins it’s the same,” there is a sense of confusion and disorientation. This disorientation puts the reader in the same position as the poem’s speaker.